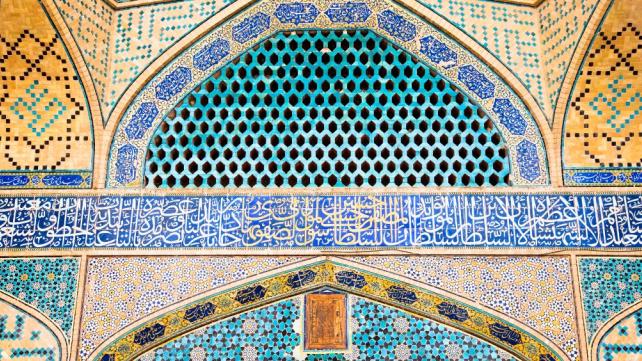

Imagine a world where religious art was centered on visual interpretations of the unseen. God was rendered into visible form to be worshipped, while saints and angels filled canvases, stained glass, and sculptures that adorned houses of worship. For centuries, the intersection of religion and art meant representing the Divine in human or symbolic form. Then came a faith so revolutionary that it rejected such imagery altogether. Islam demanded the removal of idols and images, teaching instead that ihsan, or excellence in worship, meant knowing that although we cannot see God, we are ever aware that He sees us. In response, Islamic art replaced depictions of beings and divine imaginings with intricate geometric patterns, flowing calligraphy, and vibrant floral motifs that surpassed the artistic achievements of their time. In this way, Islamic art itself became a form of activism, challenging norms, redefining spirituality, and leaving a legacy that still inspires today.

It is evident that Islamic art was never simply about decoration, but devotion. Islamic art reflected a theology that resisted idols and instead centered beauty, harmony, and remembrance of God. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art explains, “As it is not only a religion but a way of life, Islam fostered the development of a distinctive culture with its own unique artistic language that is reflected in art and architecture throughout the Muslim world1.” That artistic language became a form of activism in its own right, rejecting imposed images of God, saints, or kings and instead giving the world a visual vocabulary rooted in tawhid or the oneness of God and ihsan. That same artistic language lives on while increasingly taking on new dimensions. Islamic art lives on as activism.

Across cultures, artists have long used their creativity as a form of resistance, a way to challenge injustice and amplify the voices of the marginalized. This is often called protest art, and it intentionally unsettles, provokes, and demands change. But art is not limited to protest. Art can also be educational. It can adorn textbooks, flyers, postcards, or t-shirts. It can convey a message with a single image, a bold design, or an intricate piece of calligraphy. Visual art catches the eye and makes ideas more palpable, allowing complex concepts to be absorbed quickly and remembered longer. For Muslims, both protest and educational art carry the potential to transform hearts and minds, aligning with the Quranic principle of calling to truth with wisdom and clear statements. Allah says:

“Invite ˹all˺ to the Way of your Lord with wisdom and kind advice, and only debate with them in the best manner. Surely your Lord ˹alone˺ knows best who has strayed from His Way and who is ˹rightly˺ guided.” (Quran, 16:125)

One of the ways Muslims can embody this divine call to wise and impactful communication is through art. As public narratives continue to overlook or misrepresent Muslim experiences, art empowers young Muslims to speak truth, push back, and reimagine a more just future. Unlike speeches or academic essays, visual art crosses language barriers and communicates in a way that resonates instantly with the heart. Digital design, painting, graffiti, murals, sculpting, fashion, jewelry, and even toys have become creative tools to amplify justice, celebrate identity, and confront oppression.

Take the example of Muzzy, a brand founded by husband-and-wife duo Karter and Doaa Zaher. Inspired by their journey as new parents, they created books and toys that not only celebrate Muslim identity but also raise awareness about global struggles. Their Palestine Mina Doll channels 100% of its net profits to HEAL Palestine, a humanitarian organization. In addition, their Hijabi Queens mural initiative is transforming city walls in places like Los Angeles, New York, and Atlanta into bold, colorful tributes to Muslim women since 20222. These works of art are making a bold statement of representation, belonging, and hope for young Muslim girls searching for role models.

Another example of protest and educational art is found in the work of Alison Kysia, a Muslim woman ceramic artist who uses clay as both a medium of beauty and resistance. Rooted in the Quranic reminder that humans are created from clay, her sculptures and vessels embody both spiritual reflection and social engagement. Kysia describes her pieces as “visual dhikr” or reminders of love, justice, transformation, and the interconnectedness of creation while simultaneously pushing the boundaries of what is typically defined as Islamic art3. One of Kysia’s projects, 99 Clay Vessels: The Muslim Women Storytelling Project, emerged during a period of intense anti-Muslim bigotry. Inspired by her series of ninety-nine vessels representing the names of Allah, Kysia invited Muslim women to participate in online retreats and create their own art that captured their struggles and resilience. This collective effort, completed during the global COVID-19 pandemic, became a space of healing and a testament to the power of art as resistance.

Muslim youth are also doing their part. Muslim Manga is an organization that harnesses the power of manga to create positive change in perspectives about Muslims and Islam for new generations. Muslim Manga was founded by second-generation American Muslim artist and teacher, Hamed Nouri, but consists of a team of “creative professionals, authoring Japanese-style comics so that Islam’s true message can be more easily understood.” Through their platform, young people can read community-submitted manga, participate in artistic challenges, create content, and network with peers who share their love of art and comics. Muslim Manga admins emphasize on their site that, “We try to make big change, even if it is with one small step at a time!4” Their approach makes activism accessible, fun, and collaborative for children and teens, showing that art can be both a form of expression and a tool for social awareness from an early age.

Other grassroots initiatives also show how simple artistic expressions can spark awareness. In Islamic conferences and mosque events, young people have been seen making dhikr beads in the colors of the Palestinian flag, displaying their Islamic calligraphy creations, or selling rubber bracelets inscribed with Islamic reminders, using these small but meaningful items to raise funds and inspire solidarity. These acts may seem modest compared to murals or large-scale projects, but they carry the same essence of using art as a vessel for activism.

Undoubtedly, we are living during an artistic revolution, where Muslims around the globe have powerful, innovative tools at their disposal to create modern works of art that inspire change. From murals and sculptures to comics, digital media, and handcrafted objects, these forms of creative expression continue the centuries-old Islamic tradition of producing art that educates, uplifts, and challenges oppression. The impact is all around us, in museums, on city walls adorned with Hijabi Queens, and stored in the storytelling vessels of Muslim ceramicists. We can be part of this movement by encouraging young people to tap into their creative genius and draw inspiration from the artists of the past. Hopefully, our children can continue their legacy by filling our world with messages of hope, justice, and faith.

Add new comment