As parents, we all want our children to feel safe, respected, and included wherever they go. Yet bullying continues to affect many young people, and in Muslim spaces it can sometimes be tied to anti-Blackness. Bullying is defined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as unwanted, aggressive behavior that involves a real or perceived power imbalance and is often repeated over time1. In the context of the Islamic community, anti-Black bullying is a form of racialized bullying that targets explicitly Black Muslim children, usually drawing on harmful stereotypes or biases that have been passed down in families and societies. Understanding how to prevent and address this issue is essential for raising compassionate children and building stronger communities that reflect the Prophetic model. In his farewell address, Prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, left us with this precious guidance:

“O people, your Lord is one and your father Adam is one. There is no virtue of an Arab over a foreigner, nor a foreigner over an Arab, and neither white over black nor black over white, except by righteousness.” He then asked, “Have I not delivered the message?” His companions replied in the affirmative, to which he stated, “Let the witness inform those who are absent.” (Shu’ab al-Iman 4706)

Despite this clear message of equality and brotherhood, our communities continue to struggle with racial bias and exclusion. It seems that we have strayed from his final reminder and failed to pass on his teachings to the next generation. To help us reflect on how to correct this deficiency, we spoke with Ustadha Rukayat Yakub, a scholar and educator whose research focuses on anti-Blackness in U.S. Islamic schools and centers.

Yakub’s personal experiences as a community leader inspired her to dedicate her work to creating inclusive environments where every child feels seen and valued. She is currently pursuing a doctorate in Islamic leadership and continues to collaborate with educators and faith leaders to ensure that Muslim spaces nurture a sense of belonging. In this interview, she shares her insights into the realities of bullying, resources for prevention, and practical advice for parents and teachers. Yakub’s interest in researching anti-Blackness began while she was leading study circles, where she noticed that issues of racial injustice were often dismissed or avoided in Muslim communities. She witnessed firsthand how tragedies that deeply impacted Black communities were not given consideration or space for collective mourning. These experiences fueled her determination to connect Islamic teachings on justice with the lived realities of race in America. Reflecting on this, she explained, “If we understood the history of this country, we’d have more empathy, and instead of just not knowing what to do, or exiting from a space, we would be willing to find out more, to ask questions, to be curious, and to actually care about these issues.” Her passion eventually led her to design courses on race, justice, and poverty for Muslim institutions.

Anti-Blackness in Islamic Schools

In her preliminary research on anti-Blackness in Islamic school settings, Yakub found troubling patterns. Many Black Muslim students reported feeling invisible, disrespected, or mistreated. Some endured direct insults, being called names like “slave” or other derogatory Arabic terms. Others experienced more subtle forms of exclusion, where their identity was not acknowledged or valued. When asked if she felt her teachers and peers respected her culture as a Black Muslim, one high school student said, “They did not even know there was a culture to respect.” Yakub urges the Muslim community to reflect on the magnitude of this issue. Bullying rooted in anti-Blackness carries a weight far heavier than childhood teasing. It sends the message to children that they are somehow inferior, unworthy of respect, and undeserving of love and compassion.

Anti-Black bullying differs from other forms. Yakub explained that while bullying is unfortunately common among America’s youth, bullying tied to race and identity strikes at the core of a child’s humanity. When Muslim children use skin color or heritage as an insult, they not only harm their peers but also reject the diversity that Allah created. She said, “This is the kind of bullying that is linked to a disregard for an entire people based on the color that Allah gifted them. Just like the child being insulted, the one doing the bullying has also been gifted by Allah with a color, a culture, and a story.” Racial bullying reflects attitudes learned at home and in the community, where anti-Blackness may be passed down unconsciously or deliberately. Unlike other forms of harassment, anti-Black bullying diminishes a child’s dignity and undermines the Islamic principle of honoring all people. In fact, anti-Blackness and racial discrimination are an insult to the Creator of all human beings, who diversified humanity as a sign of His Majesty and Wisdom. Allah says in the Quran:

“And one of His signs is the creation of the heavens and the earth, and the diversity of your languages and colours. Surely in this are signs for those of ˹sound˺ knowledge.” (Quran, 30:22)

Advice for Educators and Caregivers

So, how can educators and caregivers address bullying tied to anti-Blackness? Yakub emphasizes that punitive measures alone are not enough. She said, “They have to recognize their own biases. They have to do some real introspection. If we can't recognize what is wrong in our own selves and we're leading the space, what do we expect our kids to do?” For her, real change occurs when children are guided to view the world through the ethical lens of Islam and understand that they have a choice in how they treat others. She mentioned the importance of the middle school years, especially when children’s sense of justice is heightened. Educators and caregivers must nurture that instinct to help young people expand their concern beyond themselves and toward building compassionate communities.

Teachers play a central role in creating safe spaces for all students. Yakub recalled a troubling incident she heard happened to one student in an Islamic school classroom, “Someone said to her, ‘Come here, my slave.’ And this happened recently. And the thing is that our kids, Muslim children, speak like that, and nobody is really sitting down and telling them that this is not acceptable.” She stresses that without self-reflection and an understanding of anti-Blackness, even well-intentioned teachers may overlook or excuse such harmful behavior. Studying the history of racism in America can help educators recognize when discriminatory attitudes appear in the classroom so they can address them immediately. Additionally, schools need clear, zero-tolerance policies that name racial bullying for what it is, while teaching students why such language and actions have no place in Islam.

Yakub outlines five steps families and schools can take to address anti-Blackness and bullying:

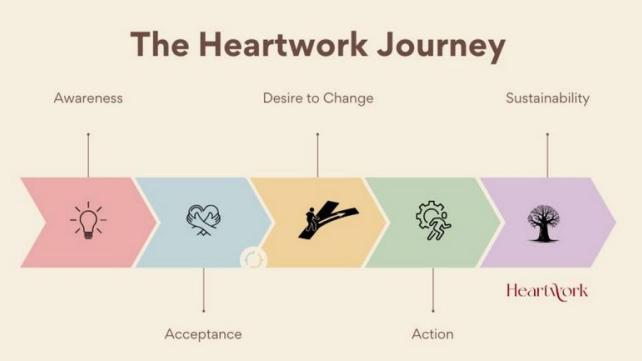

- Awareness – Learn what anti-Blackness is and how it shows up in schools, homes, and communities. Recognize that it is different from general racism and has deep historical roots.

- Acceptance – Acknowledge that bias can exist in your own heart, family, or institution. Real change begins with honest self-reflection.

- Desire to Change – Commit personally to doing the work. Transformation cannot be forced on others unless we begin with ourselves.

- Active Change – Take concrete steps, such as diversifying your family’s bookshelf with stories of Black Muslim children, attending diverse mosques, opening your door to people of other backgrounds, and introducing inclusive policies in schools.

- Sustaining Change – Keep the momentum alive. Have ongoing conversations with children, revisit your practices, and continue learning so that inclusivity becomes a habit rather than a one-time effort.

How Parents Can Help at Home

More often than not, children are learning patterns of anti-Blackness at home. Yakub noted, “The deep anti-Blackness that exists in our community is transmitted to the children. Because many of these children didn't pick it up in Muslim lands, they picked it up in their families growing up here.” It is thus of utmost importance to address racial biases in the family first and foremost. That starts with parents asking themselves some difficult questions: “What kind of books do we have in our home? What kind of masjids do we go to? Do we go to the African American masjid and attend jummah there?” Yakub added, “What would be more helpful is if you go to your spaces and reduce the anti-Blackness there. So that when Black Muslims come into your space, they can breathe.”

Yakub firmly believes that one of the most effective strategies is teaching children that they always have a choice in how they treat others. She explained that young people must be guided to view the world through the ethical lens of the Prophet’s example, rather than simply absorbing the values of the surrounding society. To model this, parents must first learn what anti-Blackness is and accept that it can exist in their homes and communities. From there, they can take intentional steps, such as diversifying their home libraries with children’s books that feature Black Muslim protagonists. Yakub recommends titles like Sister Friend by Jamilah Bigelow and All You Have to Do by Autumn Allen, which illustrate the lived realities of Black children in relatable ways. Parents can also model inclusivity by attending diverse mosques and nurturing authentic friendships across racial and cultural lines.

Through her own children’s books, like The Gift of Shaykh Ahmadu Bamba, her Heartwork workshops, and her courses on race in America, Yakub is also equipping families and schools with tools to shift harmful narratives. She is currently leading a crowdfunding campaign called Building Heartwork Spaces, which supports the development of a self-paced Heartwork training program designed to prepare Muslim educators and leaders to create classrooms rooted in safety, well-being, and belonging. Yakub’s work serves as a reminder that educational initiatives and storytelling are effective tools for creating social change.

At its heart, addressing bullying is about tazkiyyah, purifying the heart and cultivating self-love and respect for humanity. Building a child’s self-esteem and guiding them to see the good in others is a first step. Yakub said, “If a person doesn't understand who they are and what their potential is, they're just going to do whatever everyone else does. They don't understand just why they have the power to be different.” Being anti-racist takes courage, self-reflection, and a lot of “Heartwork.” When families and educators commit to this work, Muslim spaces will become places of belonging for all children.

Parents and educators who wish to learn more or support the Building Heartwork Spaces campaign can visit the following page and join the effort to nurture more compassionate and inclusive Muslim learning environments:

Add new comment